The President does and should not have the power to unilaterally make war on foreign countries, and can only do so with the consent of the people given through their representatives in Congress.

Yet, at 2 a.m. Caracas time on Saturday, U.S. forces struck Venezuela’s capital with at least seven explosions. Delta Force operators captured President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, extracting them from the country to face criminal charges in the United States. All of this happened with no congressional authorization, no declaration of war, and importantly, no public debate. Maduro’s removal is welcome, but the lawless precedent it sets is dangerously alarming.

Maduro is a narco-trafficking dictator who rigged an election and pushed 7.7 million Venezuelans into exile. He deserves prosecution. Donald Trump’s operation to capture him is nonetheless unconstitutional, dangerous, and precedent-setting in the worst possible way.

Our Constitutional inheritance establishes a clear process to conduct war, ensuring that it is legitimate to the American people and that there are no abuses of power. If we don’t reassert constitutional limits now, we’re allowing any president to wage war on any “narco-state” without congressional approval, as long as the operation is fast enough. That’s not a power Trump should have. Neither should his successors nor any of his predecessors.

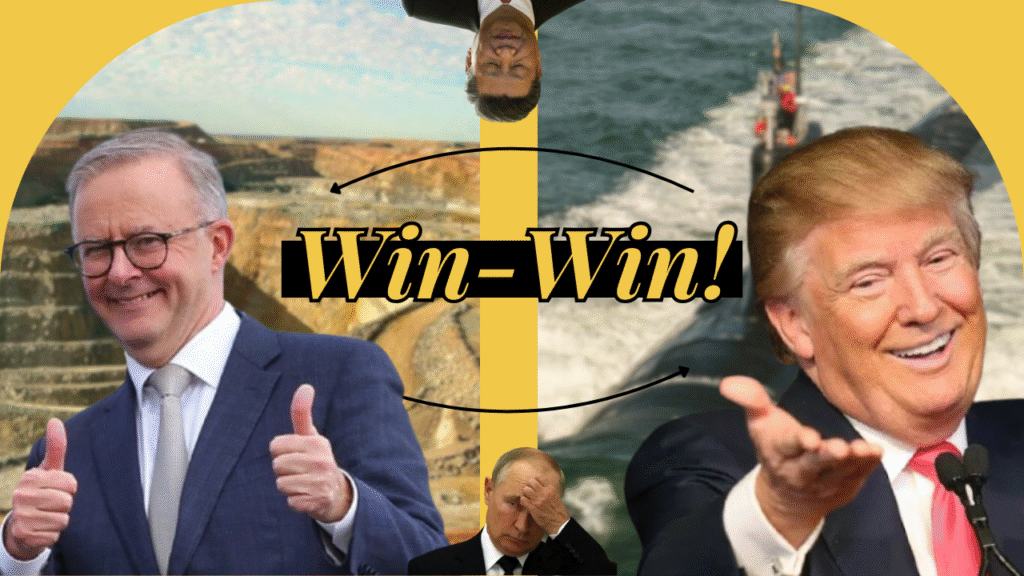

The strike was the culmination of a four-month military campaign, all conducted without congressional authorization. Since September, U.S. forces have destroyed more than thirty boats in the Caribbean and Pacific, killing at least 115 people. In December, the CIA conducted a drone strike on a Venezuelan port facility and Trump ordered a naval blockade of Venezuelan oil tankers. Then came Saturday’s assault on Caracas.

These weren’t law enforcement operations, but acts of war. Lawmakers from both parties raised objections, which the administration has ignored. Their legal theory is that Saturday’s strikes executed an arrest warrant issued in 2020. But arrest warrants don’t authorize military strikes on foreign capitals, and certainly not on foreign civilians. The Marshals Service executes arrest warrants and the military wages war. Trump used the latter to accomplish the former. When the United States violates international norms against unilateral regime change, even against dictators, we lose moral authority to object when China or Russia claims to do the same.

Maduro was terrible. He was indicted on narco-terrorism charges, international observers confirmed he rigged the 2024 election, and under him, Venezuela has become a humanitarian catastrophe. We should by no means mourn his removal. But we must question the means by which it happened.

The Constitution doesn’t have an exception for bad guys. The war powers clause exists because the Founders knew presidents would always have reasons for war, sometimes even good ones. In writing Article II, the Founders explicitly changed the text to be defensive directly towards the American homeland, with foreign affairs being under the joint-stewardship of Congress. The Founders did not want to ‘“deny the President to respond to a surprise attack” nor “to give the President the general power to initiate hostilities.” Congress’s involvement exists to make war decisions better, not just slower.

Now, we as a country must decide our commitment level to a decision Trump made without us: making the plan for Venezuela’s transition, preparing for a possible civil war or refugee crisis, and deciding our level of responsibility.

These are not questions a president gets to answer alone. The American people, through our representatives, should be able to decide if a military intervention is worth the costs and risks before it’s over. Congress must act immediately. Both parties have raised objections to Trump’s boat strikes and Venezuelan operations. It’s time to move to action. We need to hold hearings, demand legal justification, and pass new restrictions on unilateral military force.

Having intervened, we now have a moral responsibility for Venezuela’s transition. Maduro’s removal creates the opportunity for Venezuelan democracy, but only if we support the people and leaders of the country, not our own military occupation.

Broader principles matter more than the situation in Venezuela. Constitutional processes aren’t obstacles to good policy; they’re what make good policy legitimate. Trump may have removed a dictator, but he’s established a leader in the United States that can unilaterally wage war whenever it can be framed as law enforcement. If we are to defend liberty at all ends of the earth we must start with a liberty-based defense of it, by following our constitution’s clear rules.

Nicolás Maduro’s capture will likely be celebrated in Caracas and condemned in Moscow as well as Beijing. Americans should be glad he’s gone and alarmed how it happened. Good ends achieved through lawless means aren’t victories, they’re dangerous precedents. If we accept that presidents can bomb foreign capitals to execute arrest warrants, we’ve conceded that the war power, the most significant check on executive authority, means nothing. The next president will remember this precedent. So will our adversaries. We should be glad Maduro is gone. We must insist this was wrong.