Implementing decentralized identity technology can restore trust and property rights in Venezuela, empowering individuals, reducing bureaucratic corruption, and fostering economic development.

By most metrics, Venezuela has the world’s worst economy and political environment. Many of these problems stem from a single root cause: dysfunctional property rights: Venezuela has one of the weakest scores on the International Property Rights Index, 1.8/10, and is the 125th country on the list; disrespect for private property is institutionalized via legal mechanisms such as the “Social Function” of property; firms must wait 230 days to legally operate; the constant malfunction of the identification system of the government authority (SAIME); and general distrust of the electoral system.

Venezuela is at a crossroads. The current path will lead to ruin, but privatizing the economy too quickly can also lead to ruin. For example, botched privatization efforts in post-Soviet Russia led to hyperinflation, civil conflicts, and the rise of Vladimir Putin. Today, Russia still has unclear property rights. To avoid ruin, Venezuela doesn’t just need legislative and constitutional reforms, It needs technological innovations that outright overthrow the misdirected incentives of the bureaucracy in place.

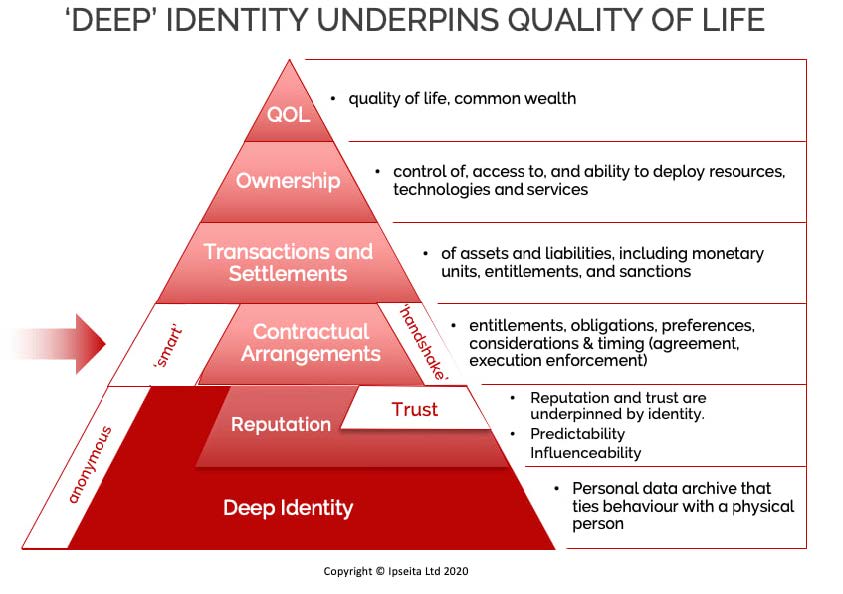

Such technological innovation must address the basis of trust: identity, that is, the unique constellation of attributes and claims that define an individual or entity, which can be acknowledged and defended through their mere existence. Private property cannot exist if it is untethered to the identity of a citizen or group of citizens.

Currently, the state assumes the responsibility to manage the trust mechanisms for property and identity. But it does so inefficiently and to dubious ends. Stata administration is no longer necessary with new technological advances and the internet.

With cryptography-based decentralized identity (DID) solutions, also called Self Sovereign Identity (SSI), trust can now be managed by the individual. This is significantly more efficient, more moral, and more cheaply implemented in Venezuela than expecting perverse incentives for corrupt bureaucrats to disappear.

To illustrate this problem and its alternative solution with SSI, consider a real-life example of property rights being violated due to a lack of trust. Melquiades Alvarado is an 87-year-old man who bought an apartment in Caracas in 1979. Due to the recent economic crisis and his wife’s (92) senile dementia, he decided to rent the apartment. Thus, he would be able to afford his and his wife’s living expenses. But doing the paperwork to legally rent in Venezuela is quite a time and energy-consuming task for an 87-year-old man. So he delegated the power to use the property to his son, this way they managed to successfully rent it to a lady called Jemina, who turned out to be a counselor of the municipality.

Since 2018, everything seemed to work until October 15th, when Melquiades discovered that his apartment had been sold to Jemima’s mom. Melquiades didn’t consent to this transaction; he fought for months with his son to prove that his son didn’t sell the property and succeeded, but Jemina’s influence on the state official allowed her mom to remain. Melquiades resorted to uploading a series of videos explaining his situation that go viral on X (formerly Twitter), in these videos he calls for the Attorney General of Venezuela (Tarek William Saab) to intervene in these irregularities. The attorney general was misled to think Melquiades’ son consented to the transaction but, after intense pressure on social media, Tarek finally restituted the property to Melquiades.

The first problem is addressed by DID, since Melquiades is still lucid and knows how to use DID, he wouldn’t have needed to delegate the property rights to his son. With all the necessary credentials to rent, he would have been able to authenticate with a simple biometric verification, even without leaving his home ( provided he had an internet connection). Second, let us suppose that Melquiades decided he doesn’t know how to use DID tech, but he could delegate to his son only the availability to rent the apartment, and not to sell. If he ever wanted to sell, Melquiades would have to explicitly authorize the transaction with biometrics. This would also avoid forgery of his son’s authority or a third party manipulating property records to their benefit. Third, let us suppose that Melquiade’s son actually could sell the apartment without his father’s consent. Even if Jemina can forge his biometrics, she would have to do so with his device; it would be impossible for her to manipulate registries to transfer the property rights from Melquiades to herself. Fourth, let us suppose that Melquiades’ son and Jemina are actually in league to sell the apartment and leave Melquiades out of the transaction. Melquiades would be able to prove that he just delegated to his son the use of the property, thus he must receive money from this transaction. It would be a matter of making the complaint with enforcement institutions, providing cryptographic proof that his property has been transferred without receipt of compensation. The enforcement institution would promptly move to protect his property rights, instead of Melquiades having to appeal to social media to pressure institutions to do their job.

DID technology aims to implement the digital counterpart of a physical wallet and document folders. Storing and protecting data provided with cryptography provides endless use cases for information that can be used similarly to physical IDs to identify people in in-person scenarios, like during a police check, and to authenticate credentials such as: driver’s licenses, passports, vaccination credentials, non-fungible tokens (NFT) representing ownership of assets, smart contracts, etc.

DID technology could also be used for electoral purposes and this potential has led many countries to invest a considerable amount of resources to develop solutions, as seen by Europe, Canada, South Korea, and the United States.1

1 Europe has the ESSIF, EBSI, and the eIDAS 2.0 initiatives; Canada has the Digital Identity & Authentication Council of Canada (DIACC); South Korea has the Decentralized Identity Alliance,USA has the mobile driver’s license framework in the ISO 18013-5 standards lead by Apple.

One particular technology, Key Event Receipt Infrastructure (KERI) answers all of Venezuela’s core technological needs. It is an open-source protocol released in 2014 that is now widely used in the European Union and elsewhere. It is fully decentralized: it does not require any databases or blockchains. Furthermore, with this protocol, it is possible to create, rotate, delegate, and revoke credentials that would solve the problems presented in the case study.

Given present conditions, implementing such a solution would require private i nvestors to do the following: hire developers of the front end of an app; consulting law firms specialized in smart contracts to establish a seamless process for private property transfers; partnering with NGOs committed to service community lacking access to smartphones—similar to the Digizen’s experiences in Papua New Guinea or a simple phone call as is the experience of Agros Tech in Perú; invest in high-quality marketing to position the decentralized identity and private property solution as the most efficient in Venezuela; and complement these with a monetary incentive program to boost adoption. All of these efforts would be swifter if government endorsement is given, but that is rather unlikely unless there is a regime change.

This solution would require little to no maintenance and, more importantly, would strip the government of the power to control the identity of individuals and the proofs of ownership. DID creates not only a strong institutional environment to protect property rights, but a marketplace for governance. Since DID tech and especially KERI are protocols, they can be used as the basis for developing frameworks of trust for other institutions