Dillon Bergmann

When thinking of hubs of Organized Crime in America the cities of New York, Chicago, and perhaps Las Vegas. Looking further, perhaps one could say New Orleans, St. Louis, Boston, Los Angeles, or even Miami. Portland is not one of these cities. However, this does not mean that crime has not existed in these parts. The legal philosopher John Austin would note that there are two kinds of people: those who are in the habit of following the law, and those who are in the habit of not. These groups who would be in the habit of not following the law would exist in Portland, though would not be as complex as those who existed elsewhere, like the five families of New York or the “outfit” Chicago. Instead, these groups would inhabit the “North End” of Portland, present-day Old Town Chinatown. They would offer themselves to be a center of libertine culture and vice—in stark contrast to the New England God-fearing prudent Portlanders which ran the rest of the city.

Syndicates would rise, but their fall would provide opportunities for political progressives—such as Henry Lane—who sought to change society into their own image. To do this Progressives needed to expand state capacity—the ability to have the state’s will “promulgated” or “known.” A large part of the Progressives’ rise and ability to expand state power would be through their criticisms of the Portland elites and their interactions with organized crime and other vice-ridden enterprises. This can be seen with the Dubar Produce and Grocery, which when discovered to be a mere front for an opium syndicate led to trials and investigations of the local party system, resulting in its downfall. Further, the Portland vice scandal would then shake the public’s confidence further by revealing how involved the Portland establishment was in the vice industries, and would cause the old establishment’s ouster. When combined and compared with previous history of state capacity by using the power of the city’s police force as proxy, we can then see how though not the only cause the prevalence of organized crime in the city of Portland would assist progressives in their political program of expanding state power.

Portland would receive its first (of many) city charters in 1851, when the city would be incorporated by the territorial legislature, being the first incorporated city in the state of Oregon. This newly created charter would give the city the power to regulate the conduct of its citizens, along with creating a council elected city marshall to help enforce these laws made by the city. This would show a change in the dynamics of Portland. Before, the Police would mostly be run by private entities, such as the Hudson’s Bay Company, and can be understood as part of a larger pattern of state development in the increasingly settled Oregon Territory.

The newly created Portland would not be as strong as the modern state that inhabits the area today. Far from it. Though it would possess a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, its geographic area was quite small. The marshall was also only part time, giving the city a very small police force, of only the marshall. In fact, when compared to even other western cities, the police force would remain rather small. San Francisco, for example, had 75 officers in its ranks. Chicago would have a force of 900. This was not because of the fact that Portland was small. When you adjust the police force for the population by using a simple ratio Portland still has a smaller police force than what would be expected (see table 1), with its ratio being 1.7 times the exclusive average—and given its size it would be expected that the city (in its inception) would have had two officers. Not to even mention the fact that for cities like New York and Boston, their police forces had been professionalized by this time.

Table 1: The Officers to 1850 Population.

| City | No. of Officers | Population in 1850 | Ratio |

| Chicago | 900 | 29,963 | 33.29 |

| New York | 2,000 | 590,000 | 295.00 |

| San Francisco | 75 | 34,776 | 463.68 |

| Boston | 200 | 136,881 | 684.41 |

| Portland | 1 | 821 | 821.00 |

In addition to being small, the Marshall was also in charge of tax collection and to enforce health standards. Furthermore, the city also did not establish a criminal code until the 8th city council meeting, due to a gang riot on the riverboat Goliath where no one could be charged with any crimes as there was no criminal code for them to be charged under. This shows the general lack of state capacity in the region—also showing that there was some form of gang activity going on. And with this gang activity, there was an ever-rising demand from civil society—the sum of non-state civic formal structures where people live in common such as churches, clubs, their families, and the like—to do something about it. The Oregonian, the largest newspaper in the city then and today, would frame the issue as one in which lawless gangs would ransack the poor innocent civilians with a need to protect their persons and their property.

The Oregoinian would not be a uniform voice on the matter of policing. The Oregon Weekly Times would take a more anti-police approach, opposing the expansion of a force in the city, citing the high costs. This sort of back and forth relating to the role of the state in the wider society, would become a common issue in the coming decades, with organized crime being a factor within it. One unique condition Oregon would face is the general inaction of the state. This made it the last place to receive most news, and made the people self-reliant to a degree not seen anywhere else. Combined with a large Democratic presence, led to a culture individualism, which in turn made people far less welcoming towards overtures towards expansions of state capacity.

The jail system was also comically inept. Before building the first city prison, the city would use a glorified shack in the middle of a wheat field, which had no prison guards, known as “Washington County Jail,” to house their prisoners. Portland would build their own glorified shack in 1858, to combat mounting crime in the city including gang activity, where to save on costs prisoners had to pay the city rent for their imprisonment.

As the city grew, so did the crime involved, with 257 arrests being made in 1863—three of these would be related to “immoral practice.” With this, the city would begin to allow the Marshall to have deputies to help perform the policing function. Though this would not be without obstruction. A major issue for the police department would be this kind of back and forth between the city and force about funding.

Though desiring law and order, the council did not want to have to pay for it. In fact, despite being one of the smallest forces on the west coast, the city council would try and cut funding. A further problem for the police was the fact that they would be under constant changes in directorship. From the period of 1863 to 1866, the police force would be run by a board appointed by the Democratic State Government, while being funded by the Republican city council—which resulted in frequent infighting.

Over time, the city would become more developed, with a small police force to boot. Portland was founded by New Englanders, and would have an odd mishmash of cultures, including the wildness of the midwestern spirit. Part of this New England Calvinist-Protastant inheritance was a deep respect for prudence and wise investments—which the sociologist Max Weber would call “the Protestant work ethic.” Portlanders would strive under this prudent culture for wise investments that would function well, both legal and less than legal. Portland would soon develop into one of the leading centers of commerce in the Northwest.

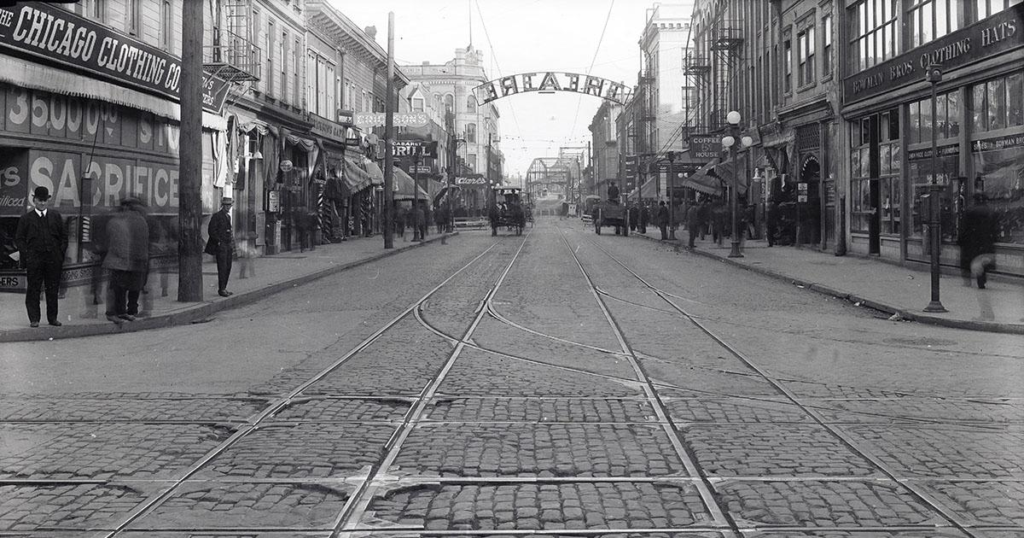

With this economic development also came the rise of a new district in the north of Portland called “the North End.” Here every kind of racket and vice known under the sun could be found. Gambling dens abounded—with most stores acting as fronts for brothel houses. Most of these houses would be run by the merchant elite, who themselves would have control over the city’s government.

Using their monopoly on the legitimate use of force, the elites of the city would ensure that the brothels would pay taxes to the city, as a kind of protection payment. This would mostly be done with alcohol licensing taxes, which would be about 30% of the city’s budget. By doing this, the city council would be able to keep taxes low for their residents, which was a constant battle to do, even if it meant at the cost of basic services. Embodying this mindset, Portland’s Mayor and wealthy merchant Henry Falling would argue that the city needed to be run like a business, which led him to successfully cut police services to only a small (wealthy) part of Portland as a means to save money, truly embodying the isolated political culture’s individualism.

Nancy Boggs, would put this kind of taxes for protection program to the test as she would set up her own prostitution racket on an abandoned old riverboat. At the time, Portland would have three separate cities with legal jurisdictions with no cooperation between their respective police forces. What Boggs would then do is set up her boat in Portland, refusing to pay taxes there. Once the city got tired of her and would try to perform a raid, she would simply move her boat to East Portland. Once East Portland would try and raid her, she would simply set sail for Albria. And around and around she went, with no one really catching on to her neat little plan until one night in 1882 when like swarms of locusts they descended—with their aim, to make the Boggs pay her taxes. Shocked by this, the old wheeler would be put up to steam, with only prostitutes being at the helm the escape looked to be going badly until the riverboat (whose crew needed little convincing) would come to rescue Boggs and her game pullet crew. It was after this debacle, that Boggs would relent and return back to shore and pay her taxes while running her illegal brothel.

These sorts of wild criminal stories would be common in Portland’s young and youthful days, and was itself part of a much larger municipal corruption problem. For example, Mayor James Chapman would publicly admit to buying the election resulting in his impeachment in 1883. But like in its infant years, civil society would not stand idle.

The end of the 19th century was an era in which people started to demand that the Government do something to fix society’s ills. This would include the moral and political corruption seen in municipalities across the country. Part of this corruption would be seen in the very produce Portlanders would consume.

One of the largest grocery outlets for Portalnder in the late 19th century would be the Dunbar Produce company. This would be owned by William Dunbar and Nat Blaum. At the time, much of the goods and people going up and down the west coast would be transported by ship—and to help reduce overhead costs Dunbar and Blaum would own the Merchant’s Steamship Company. The ships would travel from Victoria down to Portland, taking care to arrive early in the morning.

One early morning in 1892, river pilot J.L. Capels would be walking down the side of the river. He then stumbled upon three barrels. Looking inside they were full of packaging of things he had never seen before, all in Chinese. Confused, he continued to investigate until two men—William Dunbar and Nat Blum—would approach him and try to retrieve the barrels from him. Growing suspicious Capels would refuse. Blum would then offer him a dollar to thank him for finding his missing barrels. Growing even more suspicious Capels would ask for $50. Only having what appeared to be $10 in legitimate cash and about two or three counterift $100 bills, Capels would refuse the advances to surrender his find.

The bad news for Dunbar and Blum would not end there. Their ship the Wilmington would then be caught with opium by federal officials. Not a month later, their other ship’s cargo would also be found out as one of Dunbar and Blum’s associates, , wife had gotten into a feud with her neighbor—who happened to have one of the only telephones in the city. When the crew was then hiding 1,400 pounds of opium under their porch, she would promptly call the police.

Furthermore, another 900 pound shipment would go missing under a bridge near Albraia. The man tasked with finding it for three days, would also by hap and stance take a job with the Portland police two months later.

Seeing all of these smuggling crimes, and a tip from an unknown source, the federal investigators would arrive. Following the grand jury’s hearings, in 1893, thirteen people would be intiend on smuggling and corruption charges, including the head of the Oregon Republican Party and Portland Customs House Jim Lotan. Sensing the pending scandal, and upending of the political status quo, the Portland elite would come to rally around their brethren in due haste. The trial would come to be a media spectacle. Showing the interconnectedness of the elite, the foreman of the trial would be future U.S. Senator Charles W. Fulton, who was part of the same elite social club as The President of the Senate Joe Simon would be one of the lawyers of the defense, with the judge being one of his former law partners. Due to the inducement of the elite on the jury, they had procured themselves a hung jury.

The federal government would not be deterred by this. Nat Blum, by this time, had become a key government witness—a less than willing one. Each time he would take the stand his testimony would become more “creative.” Three trials would go by, with all but Lotan being convicted. Blum would go missing, and then would reappear. Some would speculate that he was trying to get a pardon from President Grover Cleveland in D.C. He would be gone so much that when he would finally disappear no one would notice his absence, with his final whereabouts never fully being known.

The old Portland establishment would be able to protect itself, notwithstanding their nefarious dealings—escaping unscathed, legally, barring a few lesser members. Though certainly their reputations all took a hit.

The 1890s would begin to see a greater mobilization of civil society against the moral corruption within the city via a series of “vice crusades,” against the vice rackets in Portland. These vice crusades were a spontaneous group of mostly middle class women and clergy who desired for more moral business practices in the city, who desired to return society to an imagined “earlier and purer age,” combined with the general pressure of hosting the 1903 world’s fair.

A large problem was simply there was no desire for reform among political elites. Joe Simon had reorganized the political bureaucracy in 1885, through a special legislative session. This would create the single most powerful force in the city until 1903: the Portland police board. The three member board would be run by the state, and by extension the party machinery. Unlike most of the U.S. the Oregon parties were solely run by the most influential merchants and lawyers in Portland, rather than by ethnic tied organizations like Tammany Hall; perhaps owing to its isolated political culture. Thus, with control over the police board, the economic elite were allowed to maintain their hold on power by controlling the use of the state’s monopoly on force and then being able to control the city by holding the council and the mayor “hostage.”

Simon would justify this political reorganization by arguing that this would lead to more effective conduct by the police. By 1900, fifteen years after the board’s creation, the number of vice houses would increase to thirty. With many of the board’s members being their owners.

Civil society would not let this be. In 1892, several members of clergy and other concerned citizens would launch an investigation into the vice rackets, and North End of the city. This was not a welcomed development to the elites. The elites would use the police board at every turn to try and obstruct the investigation, to the frustration of the clergy running the investigation. This was to be expected, looking at the trial of Lotan going on at the same time. The Portland Establishment did not want their own to be harmed, and perhaps their power over the city to be lost. Because of all the obstruction this first investigation would turn up very little information, making very little if any sort of impact. Progressives would find themselves increasingly flushed and annoyed at a lack of progress.

In 1898, Hayes Perkins, in a unpublished manuscript would summarize the sentiments of progressives,

[The lords of Portland believe in] open vice, openly arrived at. … Blocks upon blocks given up to prostitution, gambling, saloons and every dive the world holds. From First to Seventh, from Gilsan to Burnside, there is nothing but underworld. … [The local police turn] a blind eye … to vice and robbery of drunks … Then there are the endless rows of girls who play tic-tac on windows as one passes by. Tired smiles radiate as they beckon the unwary to visit their boudoirs.

The winds of change would be in the air. Henry Lane, the son of Oregon’s “founding brothers,” Joseph Lane would be elected Mayor in 1905. He would brand himself as a Progressive Democrat who would bring an end to moral and political corruption, against the entrenched and corrupt Republican establishment. Calling himself a “social hygienist” Lane would present himself as someone who was not in office for personal gain. He would be quick to accuse his fellow political elites of their involvement with organized crime and vice rackets and corruption. Nothstanding Lane’s use of loud rhetoric, Mayor Lane would accomplish little. He would veto 169 ordinances, mostly relating to city contracts. Of these 169, half would be revised by the business allies on the council.

The quintessential Portland elite—Joe Simon—would replace Lane as mayor. Quickly undoing anything Lane had done, it would be business as usual for the old Portland establishment. Business was booming. The happy days were here. But so they thought. Under the Simon administration, the Portland Ministerial Association (who had conducted the previous investigation of vice rackets) began to see the connections between the vice industries of Portland and the establishment—especially Mayor Simon. And so, they would begin to mobilize for the next election. Their candidate would be A.G. Rushlight.

A.G. Rushlight would win in a five-way Mayoral election. With this new victory, just over two decades later in 1911, within a month of starting his term Mayor Rushlight would begin another investigation. This second investigation would be more thorough than the last, having the backing of the state. Once more led by leaders in civil society, every block of the North End was scoured. Every building would be marked with its owner. No stone was to be left unturned.

The Commission would uncover businesses upon businesses that were mere fronts for illegal entities. The vice industry was “rampant and lucactive.” In total, the Commission would find 430 different locations in the city associated with vice related crimes. The typical vice related establishment would make $5,400 in the first year while only costing $1,000 to set up—and fines were minsqual at $250. The Oregonoian would editorialize, “We can squally face the fact that social vice is a large and powerful business and that it exists and spreads because it pays heavy profits.” As if 1912 could not get any worse for Simon and the Portland establishment, soon the woodwind of the national media would descend upon the city of Portland.

Benjamin Trout would be arrested on November 8. He would not be arrested for anything major. But his integration would revival a flurry of homosexual behavior in the city. Portland’s mainstream had not known gays, outside of their fantastical potryal in the media during the Oscar Wilde trials of 1895-1897. It was something only thought of as a working class phenomenon, if at all. But Trout’s testimony would paint a tapestry of the gay underworld. That same-sex relations could be going on in the middle of high society—in Portland of all places—consumed the newspaper headlines faster than a speeding Greyhound. Every front page was covered in all of the latest news, as the police dug deeper and found that the vice industry was far greater and more complex than anyone, even the Ministers had thought it to be. It would come to be so controversial that even the U.S. Congress would debate the matter.

The shocked sentiments of the year—discovering that not only was the Portland elite at the very heart of the criminal organizations within the city, and that many members of high society were doing such things as same-sex relations became something which sent shockwaves through general society. The reform Mayors, like Lane, for all their fluster had failed to meet their rhetoric. The Oregon Journal would editorialize,

It is the secret and silent gentleman who buy automobiles and mansions from the tainted profits of the underworld that are the ramparts of the system. They are the bulwarks and framework that keep the terrible structure from falling. Theirs is the influence that joins with city governments, with city officials and city police in staying the hands that try to fuigmaent and cleanse. It is money, money, money, that sustains and feeds the system.

This anger combined with the fact that this second scandal was coming from a sexual minority, gave the Progressives the window the leap through to expand state power. As F.A. Hayek would note 32-years later in 1944,

The contrast between ‘we’ and the ‘they,’ the common fight against those outside of the group, seems to be an essential ingredient in any creed which will solidly knit together a group for common action … [for] the unreserved allegiance of huge masses. From [autocrats’] point of view it has the great advantage of giving them greater freedom of action than any other positive program.

This othering can be seen in the framing of the scandal. The word “homoexual” would seldom be used. Rather, people preferred the term “the Greek scandal” or what it is now known as “the Vice scandal.” It was always sweeping the matters under the rug—ignoring the complicity of what was involved. This can also be seen in the editorial. The phrase “gentleman who buy automobiles” is meant to put “the people” (however it is defined by the Journal) against a “secret and silent” foe—which helps the reader feel activated to advance the newspaper’s agenda.

This anger would be acted upon by Progressives, who would propose a new governance system in 1913. This new system would severely limit both executive and legislative branches by merging them into a single city council that would perform both the executive and legislative functions, presided over by the mayor and four at large city councilors. The goal of this was to expand state capacity in the face of the open vice that purified the city. This new proposed charter would be adopted later that year, and would be in effect until the 2022 general election.

Furthermore, new laws and changes would be enacted to help curtail the vice industry. Firstly, the Portland criminal code was expanded to include an expanded law against vice industries. If a vice industry was found to be running on a person’s property then the city would have the right to sue to shut it down, without any proof of knowledge relating to it. Furthermore, each hotel had to have a tin plaque out in front of the building declading openly who owned that building to make it easier for people to find out who was involved with vice industries in future. Finally, the city recognized its own internal management particles, especially in the police department following a report from a New York research institute, which found the force comically incompetent.

Though Portland was not New York or Chicago, it did have some organized crime. Progressives wanted to make the city better in accordance with their political programme. Part of this was to expand the police force in the city. By increasing professionalism in the police force, as well as expanding their resources, the Progressives were then able to develop a much stronger state-apparatus in the city, to help with the development of their programme. This then coincided with a crackdown on vice-related industries. This then allowed Progressives to help eliminate, or at least limit, the effects of behaviors they thought to be immoral, such as same-sex relationships. Crime syndicates would go on. In 1956, yet another scandal would cause the slow decline of the new Portland establishment. By the 1970s, the present one had formed in its vapor. Though these new crime syndicates were not as libertine and free willing as those syndicates which came before, the spirit of the 19th and early 20th century crime syndicates lives on like Romeo and Juilet’s love though Portland’s self described “weird” culture.

References

Boag, Peter. Same-Sex Affairs: Constructing and Controlling Homosexuality in the Pacific Northwest. Berkeley, Calf.: University of California Press, 2003.

Donnelly, Robert C. Dark Rose: Organized Crime and Corruption in Portland. Seattle, Wash.: University of Washington Press, 2011.

Hofstadter, Richard. The Age of Reform. New York, N.Y.: Vintage, 1960.

MacColl, E. Kimbark., and Harry H. Stein. Merchants, Money, and Power: the Portland Establishment, 1843-1913. Portland, Ore: Georgian Press, 1988.

John, Finn J.D. Wicked Portland: The Wild and Lusty Underworld of a Frontier Town. Dover, N.H.: Arcadia Publishing, 2021.

Oregon Weekly Times (The). Sept. 25, 1861.

Oregonian (The). Aug. 24, 1912.

Oregon Journal (The). Aug. 24, 1912.

Perkins, Hayes. “Here and There: Volume 1.” Unpublished manuscript, October 1898, OHSRL, Portland, Ore.

Tracy Charles Abbot. The Evolution of the Police Function in Portland, Oregon, 1811-1874. Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1976.

U.S. Census Bureau. “1850 Census: The Seventh Census of the United States.” Census.gov. December 13, 2023, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1853/dec/1850a.html.

Weber, Max. The Protestant Work Ethic with Other Writings on the Rise of the West (4th ed.) trans. and ed. Stephen Kalberg. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.